You may have noticed an influx of film photos in the last year and I think it is time to discuss the camera itself or at least the initial one. Anytime we get a new piece of equipment I have Keltin review it for me, for this blog, because he is primarily the one behind the (film) camera. It is a bit long but I hope that you enjoy this talk of film and light.

Background

In the late summer of 2022, Laci and I happened to stumble into The Denton Camera Exchange. You, faithful reader, know that I couldn’t pass up a good camera shop. This little place was perfect. It’s charmingly messy, the real “Den-of-a-Genius” kind of place. That is a very high compliment.

There was just one problem: it’s a shop that’s dedicated almost entirely to film photography. Since I’m a child (don’t come at me) I never really go to experience film photography in any meaningful way, outside of disposable cameras.

I wasn’t totally in the dark, though. The exposure triangle that we use in digital photography was born in the film days. I know the triangle intimately, but I didn’t truly understand it; I’ll get to that. It’s hard to explain, but film has always seemed to me to be significantly more complicated and much more nuanced. Digital is an exact reproduction of the image you see. Film is not.

In today’s digital world, most of our “action shots” (think sports photography), those photos of life in motion are digital. There’s a good reason for this. Digital photography allows for very quick manipulation of settings, and the ability to shoot hundreds of photos easily. If you’re a photographer, you can get the photo from the camera to social media or post-game press release in a matter of seconds, and that is crucial.

We did, of course, take action shots with film. Photos of life in motion, especially sports photos, or shots of one’s kids playing on a summer afternoon may have more flexibility with digital, than film. But that doesn’t make them any more special.

Before I wandered into Denton Camera Exchange, I believed that film photography is best for artistic, and minimal photography. What I found there seemed to support this belief. Film is perfect for this.

The Camera

Anyway, on a high shelf at the Exchange was this stunningly beautiful, stylish, and, frankly, sexy, camera. I played with it, and I was instantly in love. One lens above the other was intriguing. In my mind, it seemed like this camera, with its smooth curves, minimal boxy shape, and emphasis on design and function, this was the kind of camera that God would make.

As stated, I knew little about film, so I wanted to sleep on it. But I knew what my decision would be. The fact that it was designed and built in 1938 only cemented my choice. I am a man that loves chalk boards (a piece of chalk never dries out), typewriters, pencils, and paper. I choose to spit in the face of the 21st century and opt for the granular insanity of doing it by hand, doing it the long way, and slowing down. In fact, I wrote out this entire thing in pencil before typing it out.

But I had to do my research. What is this camera? How much is film? How available is the film? The Internet is a perfect fountain of knowledge for “analog brained” people (hipsters, really) if you know where to look.

This is a TLR, a twin lens reflex camera. The top lens is for viewing and composing the shot. The bottom for shooting it. This camera is, specifically, a Rolleicord, which was manufactured by the Rollei corporation in Germany. The film is 120 film, and it is what is known in film photography as “medium format.” This camera gives us square photos. Medium format photography gives the user large negatives and higher quality prints than other formats such as 135, or 35mm.

We bought the camera, and I went to work on a blazingly hot weekend in early August. I learned quickly that this little box was perfect for me. But I learned how high the stakes are. One-twenty film is shorter in length than 135 film. In a 6×6 format, I get only 12 shots. They must count. There are no throw-aways.

Film and the Art of Light

I wrote in my R5 review that photography is the art of light. I want to amend that. Light is trillions and trillions of photons zooming through the air really, really, really, really fast. Light is important. If you believe in the creation story, light was literally the first thing created. A film camera captures those photons, essentially freezing them. How film works is complicated. A lot complicated.

Here’s the amendment: photography is also the art of the medium, the format, and the limitation. All of those are either lost or too easily manipulated today.

For medium, film is obviously the canvas upon which your photons are gathered. But “film” is too general. Films come in a number of sensitivities, sizes, and can either be black and white only, or color. Chemistry plays a role (ha) too, and that depends on the manufacturer. The video below shows how film works, how it’s developed, and how it fits into our digital world.

Light is not constant, even on a sunny day. It’s easy to account for this with your phone, or even an R5. All three points of the exposure triangle can be changed on a whim. The perfect photo is always at your fingertips. I love all my cameras, but taking the thinking out of art only hurts us.

Of course, film is different as it requires some forethought. Some of that is in the choice of film. ISO is the original measurement of the sensitivity of the film to light. The lower the number, the less sensitive, and the better for high light situations. Film with an ISO of 400 is what I use the most since it’s a good middle ground. The grains in the film are just large enough to be noticeable and pleasing. Plus, the limited shutter speed and aperture settings of my nearly 90-year-old camera come into play. The R5 can gloriously handle just about any setting you want. The Rolleicord cannot.

All of this I had to learn. Don’t worry, it was a dump truck of information for me too. When I started this, I knew of 135 film, instant film (like Polaroid, which we also have), and cinema film, plus whatever came in disposable cameras. In 2022, I thought that those sizes were it. To be sure, 135 film is the most widely available today and has been for several decades.

This film is so ubiquitous that its aspect ratio of 3×2 1:1.50 sets all our expectations about what a what a photo, or other media should be. It’s everywhere. It wasn’t until recently that the technology for capturing (and displaying) media allowed us to have larger and extremely rectangular aspect ratios flooding our eyes. This is especially true of smartphones. When you purchase a new phone, the camera’s default setting is to shoot a photo the entire size of the screen. But 3×2 is still the standard for photography.

For reference, even my Canon R5 shoots in 1:1.5. There is nothing inherently wrong with any of these aspect ratios. But we have to recognize that they are important. In many cases, composition is the difference between a great photo and a bad one. Knowing the dimensions of the photo you’re taking, the limitations, is a crucial part of understanding light art.

Shooting 120mm Film

This brings us to the Rolleicord and its appetite for 120 film. Since the negatives are larger, the light sensitive film is much shorter. I spent all this time talking about aspect ratios because we are used to seeing rectangles. Everything boxy is a rectangle, windows, computers, books, paper. But this camera gives me square photos in a 6×6 format, or 1:1 aspect ratio. If you know math, then you know that is a humble square.

The square poses many compositional challenges, chief of which concerns the rule of thirds. That rule states that images are more interesting to the viewer if the subject is placed in a third of the frame near one of four “hot spots,” rather than directly in the middle. The concept is easy enough to understand but devilishly hard to master. When we look at something with our eyes, we put the object of our vision in the middle of our field of view. We do this with cameras when we use them too. But the rule of thirds dictates not only the placement of the subject within the photo, but also the amount of space between the top of the subject and the top of the frame (head room) and the direction that the subject is facing (lead room).

A square can very easily and efficiently be divided into thirds, but the segments are very different when compared to rectangular photos. Squares are not common outside of math books. Rectangles are everywhere. Interesting rectangles divided into thirds give you more interesting rectangles. Humble squares divided into thirds give you only more humble squares.

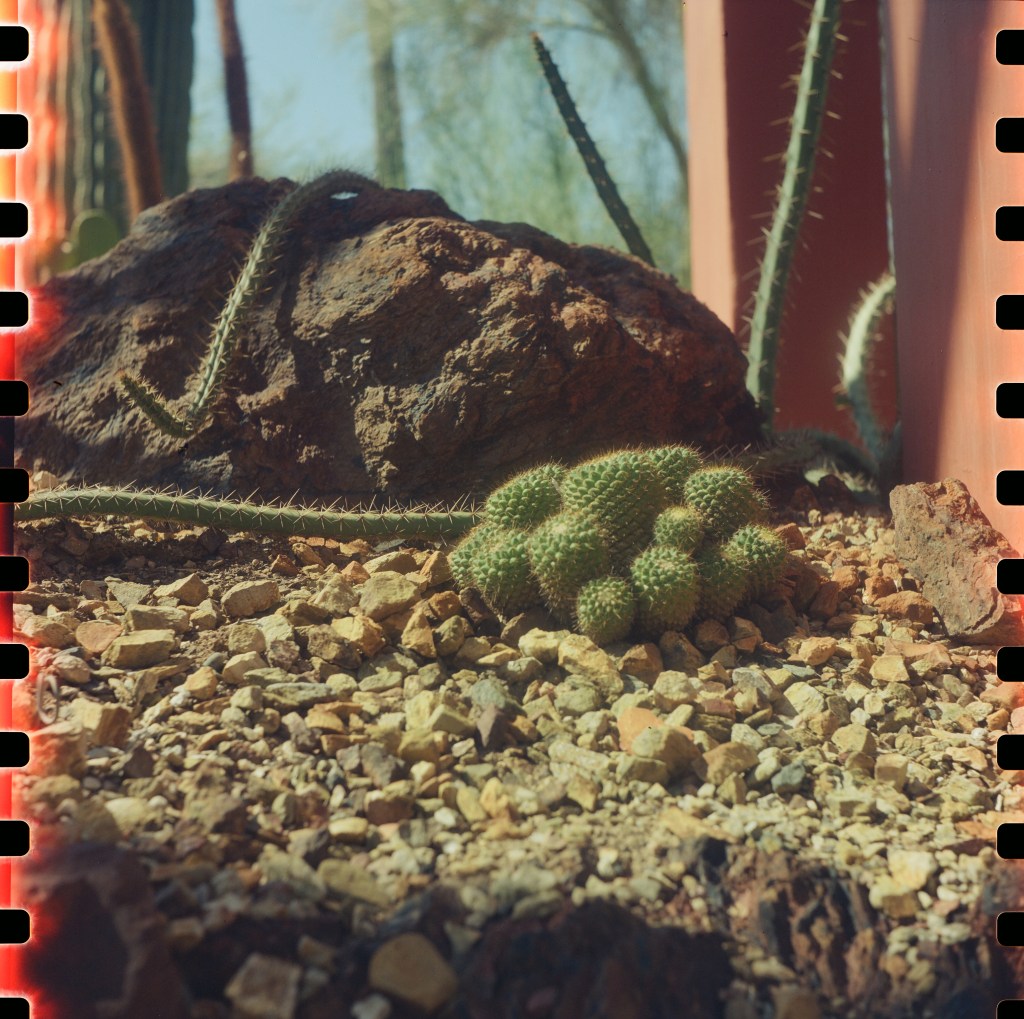

When composing photos in square format, it seems to me that the format is much better for conveying vertical space than horizontal. I don’t have a single idea why this is. If I take a square photo of a horizontal subject, it seems to be lost in an excess of foreground and sky. This image can be compelling, but it must be kept in mind.

Vertical subjects, on the other hand, are great. Again, I don’t know why. The below photo is a perfect example. The cactus is tall in real life, and it appears tall in this square photo.

Handling Film

Next is storage. With your standard and familiar roll of 135 film, the film is contained within a small metal case and would around a spool. The film is loaded into the camera, shot, and then rewound into the same cannister after the roll has been exposed. The cannister is light-tight.

One-twenty film is totally different. It involves two spools. The film is taped onto a strip of opaque backing paper and then spooled around a large plastic spool. The film crawls from one spool to the second one. There is no rewinding the spool. The end of the film has an adhesive strap that wraps around the now exposed film. Fun fact: the adhesive is the same they use for envelopes. So, you literally lick your film to secure it. Since there are two spools involved, you always have to keep track of the one you just finished. It becomes the next spool around which the next roll of film is wrapped.

But that’s only part of it. This arrangement of the film around a spool protected by paper is “hopefully” light tight. The ends of the spool won’t protect your film if you have it out in the sunshine. Some of these photos from Phoenix demonstrate that. The light around the edges did add a neat effect, but it’s not what you want.

Conclusion

Film, though, is truly magical. There was a steep learning curve for this camera and it’s very possible that this lustrous camera, film format, and all the nuances that come with handling 120 film is not for beginners to photography. All the above is part of that granular insanity I wrote about above.

Another thing to keep in mind: the image sensors on a digital camera, like my R5, are arranged in perfect rows and columns. This is why digital photos are so crisp and have well-defined lines and shapes. It’s manufactured and that’s okay. A random smattering of light sensors would be an extremely bad digital camera. The digital camera represents our want to organize things.

The magic of film, though, is how it reflects life: it’s not perfect. The film that is manufactured today is literally the best film in the history of film. But the grains in the film are crushed up bits of silver halide, an imperfect substance, crushed to imperfect bits. They are arranged randomly, and this randomness gives images life, depth, and interest on its own.

It’s here, with a hurting hand, that I realized that I haven’t said much about the camera. What is there to say? We get wrapped up in the specifications of things in our lives. We’re comparing the specs so as to always keep up with the Joneses. Our cars have this much horsepower. Our computers have that much RAM. My R5 is different from many other cameras on the market because of its specs. And that’s okay!

But it’s important to remember that the camera is from another time. The Zeiss lens is great (truly). Film grants you a lot of forgiveness on settings. If you get the settings reasonably close, you’re gonna be fine. What mattered when this camera was made was its longevity, its usefulness, and its ability to capture a worry-free photo when you needed it. The magic is the film and the eye of the artist.

I have been shooting photos for almost 20 years. But I don’t think that I truly understood photography. I might now, but I hope that this art never stops teaching me.

I hope that you enjoyed this long but hopefully enlightening review. I hope that you are enjoying my film series. See the first post here. What are your thoughts on film? Let me know in the comments.

Thank you KW Photography for allowing me to use your wonderful photos!

INSTAGRAM│TWITTER│YOUTUBE │PATREON

If you like the banner check out this design and others at Canva!

Great post. What a learning journey, I confess I am overwhelmed. I just want to take a good photo here and then, but the science and nuances are daunting. Thanks for the daunting.

LikeLike